Climate services for all

Interactive climate services illuminate different aspects of climate change

On the occasion of the EUMETSAT Climate Symposium “From Space to Climate Services: Co-creation in Action” in Darmstadt, Germany, we highlight three ways EUMETSAT data contribute to climate services.

Health impacts beyond temperature

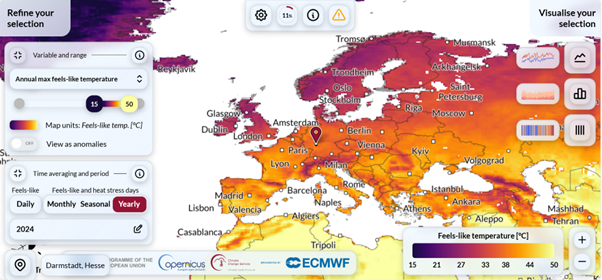

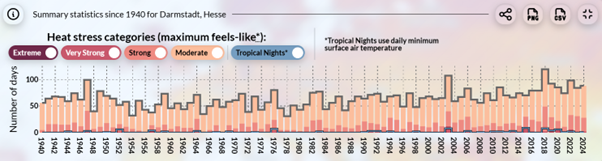

The leading cause of weather-related deaths is heat stress, with more than 61,000 heat-related deaths in Europe during the summer of 2022, according to the World Meteorological Organization. Given that climate change is expected to cause more frequent and intense heatwaves, Dr Rebecca Emerton and her team created Thermal Trace, a web-based climate service that enables people to easily access free climate data on thermal stress.

Credit: C3S/ECMWF

Credit: C3S/ECMWF

“Thermal stress is the umbrella term for heat and cold stress, which refers to the negative impacts on the body caused by exposure to extreme thermal conditions,” said Emerton, Diagnostics and Climate Monitoring Scientist at the Copernicus Climate Change Service, implemented by the European Centre for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts (ECMWF) on behalf of the European Commission.

“Heat waves and cold spells or cold snaps are types of hazards associated with increased health impacts and even fatalities, particularly in vulnerable groups. Heat stress can exacerbate underlying illnesses such as cardiovascular diseases, diabetes, mental health conditions, and asthma. Cold stress, on the other hand, brings with it the risk of frostbite and hypothermia.

“The important thing to keep in mind is that thermal stress is not just about temperature alone. It is a complex phenomenon, particularly when you've got the reaction of the human body to the environment. There is a range of other factors involved besides temperature, including wind speed, humidity, sunshine, thermal radiation, and also how the human body reacts to the environment.”

Through Thermal Trace, people can explore notable events such as the 2024 summer heatwaves in Europe that claimed more than 60,000 lives or the extreme cold snap in the Nordic countries in early 2024, when temperatures in Finland, Sweden, Norway, and Iceland plummeted to a feels-like temperature of below -40°C and compare these events with conditions during previous years.

“I think heat stress and cold stress are ways that people can understand the impact of climate change on themselves,” said Emerton. “When you have a summer heatwave, for example, it spurs people to understand what is going on and compare it to past events. For example, we had a very hot summer in the UK this year which a lot of people compared to the infamous very hot long summer of 1976 when we had extreme heat and drought.

“The data in Thermal Trace can help people understand and compare these types of events with real data that are consistent across time and space. I think there are a lot of different questions Thermal Trace can answer to really help people understand how the weather and climate are affecting them.”

Drought’s memory

In 2022, Central and Southern Europe experienced the most extreme drought since 1960, according to a team of researchers from the Helmholtz Centre for Environmental Research. Wildfires blazed in France, Greece, Italy and beyond, crops failed across Spain and Portugal, and Italy implemented emergency water-use restrictions.

“Drought has a memory, and it accumulates,” said Tetzlaff. “If soil gets dry and then there is one rain event, the soil will not regain its moisture substantially. And this is why if there is a drought in July and we see it is not going to rain a lot, there is a very large likelihood to also have a drought in August.”

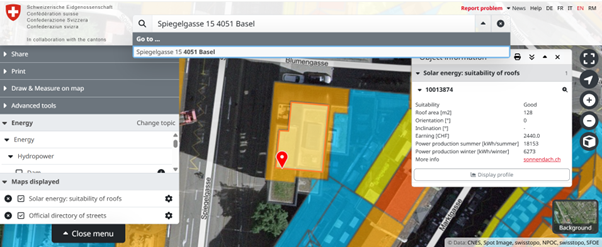

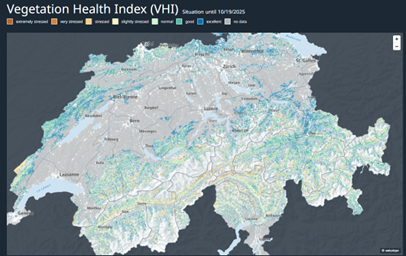

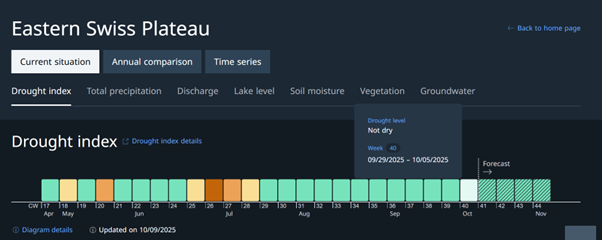

In an attempt to better inform people in Switzerland about impending drought, Dr Tetzlaff and Dr Vincent Humphrey, drought expert at MeteoSwiss, collaborated with Swiss federal agencies to create the National Drought Platform. An interactive map provides users with a ranking for each region on a scale ranging from not dry to extremely dry. It incorporates a wide range of data, including precipitation, snow cover, the water level of rivers and lakes, the volume of groundwater, soil moisture, and vegetation.

“This is our first climate service where we actually use satellite data to issue warnings in Switzerland,” said Tetzlaff. “This is where for the first time we also fully exploit the entire climate data record from the Meteosat satellites. We go back to 1991 because we want to know if, for example, the 2021 summer was particularly warm compared to the climate normal in Switzerland, that is, the average weather over the 30-year standardised period from 1991 to 2020.”

Credit: Swiss Confederation

Data from EUMETSAT satellites play a key role in the National Drought Platform through a vegetation health index, a combination of both vegetation and heat observations, which complement observations from the Copernicus Sentinel satellites operated by the European Space Agency (ESA).

“For the land surface temperature, it was important to have hourly measurements stretching back to 1991,” said Tetzlaff. “But the ESA-operated Sentinel satellites do not go back that far. We wanted to find out when it was unusually warm, which we were able to retrieve from Meteosat satellites. And by doing this, we were able to make our drought platform a true climate service. This is very important for us because we want to understand if the temperature anomalies we have been seeing are becoming more frequent in the future.”

Author:

Sarah Puschmann