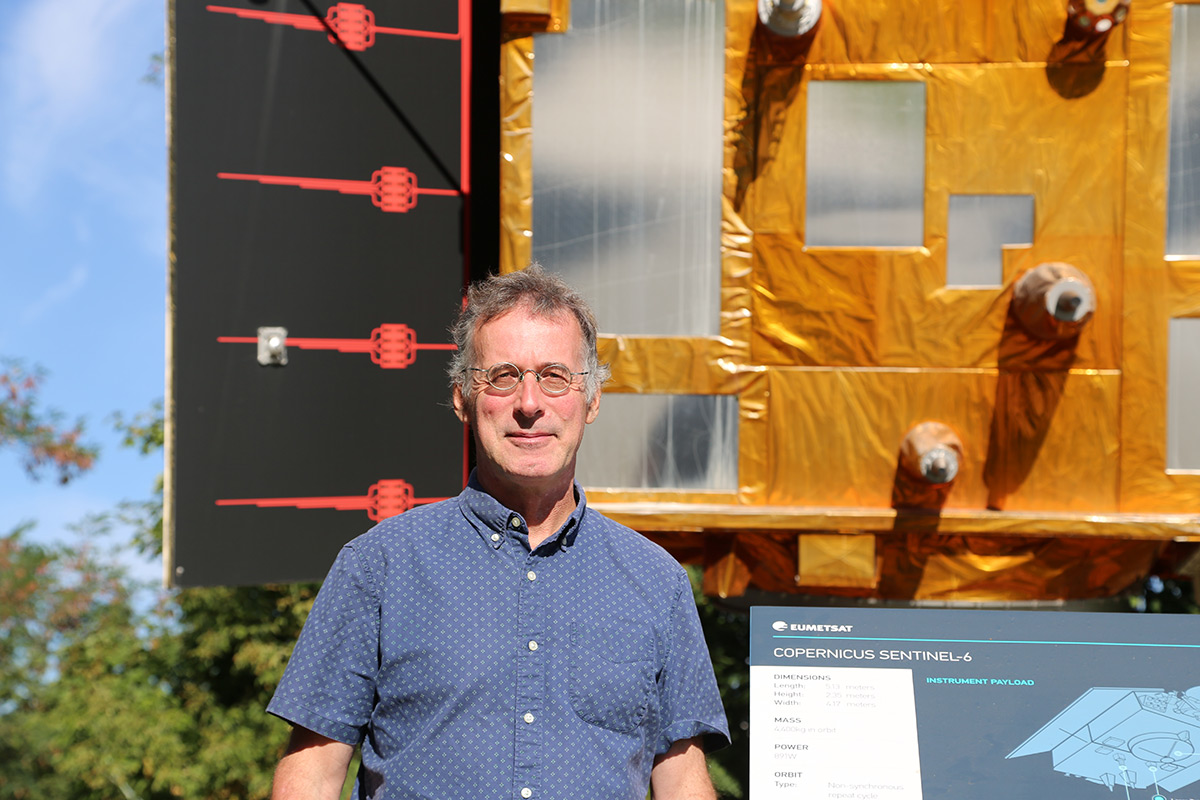

Building this model enables him to explore the ocean from another angle than he does through his work. As EUMETSAT’s Altimetry Project Scientist, Scharroo is responsible for defining the inputs for the Copernicus Sentinel-6B satellite, planned to be launched later this year. The main instrument on board is the Poseidon-4 altimeter, which sends radar pulses down to the ocean. They reflect off the ocean surface and travel back to the satellite. Depending on the time this round-trip journey takes, it is possible to determine a number of features about the ocean including its height, the average height of the highest third of the waves, and wind speed along the sea surface.

A number of factors affect the speed the pulses travel that Scharroo and his team need to account for. The satellite will orbit at 1,336km above the Earth in the outermost layer of the ionosphere, the highest part of the atmosphere. Radar waves emitted by the altimeter pass through this layer where free electrons refract them, and through the lower layers of the atmosphere, where their speed changes depending on the pressure and humidity. By correcting for these variables, in addition to changes in sea level due to ocean tides, Scharroo and his team ensure that the altimeter measurements are as accurate as possible.

They are also hard at work ensuring continuity between the observations from Copernicus Sentinel-6B and its predecessor, Copernicus Sentinel-6 Michael Freilich. The latter satellite currently has the important role as the global reference mission for satellite ocean altimetry – that is, it is the satellite against which all other ocean altimeters are calibrated. Because Copernicus Sentinel-6B will carry on as the reference mission after Copernicus Sentinel-6 Michael Freilich retires, it is crucial that the measurements from both satellites align.

“This part of our work will start seriously after the satellite is launched,” said Scharroo. “To make the comparison easy between the observations from the two Sentinel-6 satellites, we are flying them in very close succession – Sentinel-6 Michael Freilich will follow Sentinel-6B by just thirty seconds. In the space of those thirty seconds, practically nothing in the ocean or atmosphere changes. And what does change, like the ocean tides, we can correct for.

“For six months we will align the measurements of the altimeters on both satellites. And on top of that, the electronics in each altimeter are duplicated. So, we will test both sets of electronics in the Sentinel-6B altimeter. That way, in the unlikely case that one were to malfunction and we would need to switch to the other one, we will still be able ensure continuity in the measurements.”

Sentinel-6B will carry on global sea level observations begun in 1992 with TOPEX-Poseidon, and continued with Jason-1, Jason-2, Jason-3, and now the Copernicus Sentinel-6 satellites.

“At the beginning of this period, sea level rise was about around two millimetres per year,” said Scharroo. “Now, it is about five millimetres per year. The rate of change has doubled. In low-lying places that do not have the resources to build dikes, such as small islands in the Indian Ocean, the continued accumulation of this sea level rise is life-threatening.

“Hopefully, at some point, we will reduce the amount of carbon dioxide released into the atmosphere. Then maybe in the coming years, the sea level is not going to keep on rising five, six, seven millimetres per year. Maybe it will get stuck at five, go back to four, and in the end, I hope the sea level will actually stop rising.”

Author:

Sarah Puschmann