User Forum in Africa

15th EUMETSAT User Forum in Africa will be held on 13-16 September 2022 in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania.

How satellite data help communities manage fires in Tanzania

Tanzania’s Serengeti National Park is home to one of the greatest annual migrations on Earth. Each year, around two million wildebeest, zebras, and gazelles gallop across the seemingly endless landscapes of grasslands, woodlands, and estuaries, headed in the direction of the Maasai Mara reserve.

Wildfires are an integral part of the dynamic savannah ecosystem. They help to keep its vistas open by suppressing the growth of thorny shrubs. They influence the composition, structure, and patterns of vegetation. They also nourish the soils and shape the flows of water resources critical to ecosystem wellbeing.

Yet pressures from human settlements on the edges of the reserve, such as the expansion of agriculture and pastures, have threatened to throw the Serengeti ecosystem off balance. Studies indicate that in past decades, animal migrations have been disrupted, soil fertility reduced, and populations of some species have plummeted.

“Ecosystems such as savannahs cannot exist without fire; wildfires are as essential as sun and water,” says Kekilia Kabalimu, a principal cartographer, and geographic information system and remote sensing expert at the Tanzanian Ministry of Natural Resources and Tourism.

“Satellite observations show savannah landscapes dependent on fires are seeing less of them. Settlements and farms are acting as firebreaks. Livestock are consuming vegetation that would otherwise burn, while the buildup of shrubs can lead to larger, unsustainable wildfires later on.”

Diverse sets of satellite data delivered to users in Africa by EUMETCast support the coordination of conservation strategies. They facilitate ecological assessments of landscapes in the context of fire risk, detailed assessments of burned areas, and provide near-real time information on fire activity.

“These data are vital not only for managing fires where they are beneficial, but suppressing wildfires where they are not,” Kabalimu explains.

Tanzania has around 48.1 million hectares of forest and woodland cover, blanketing more than a quarter of the country’s land area. However, the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations estimates that between 1990 and 2010, the country lost up to 1% of its forests each year from wildfires.

It is in forest areas in particular where unwanted wildfires can destroy essential habitats, kill animals unable to escape, undermine nutrient cycles, and ruin the lives and livelihoods of local people.

“Economic development is opening up many forest areas, and increasing the threat of wildfires,” says Kabalimu.

“When forests are fragmented, moisture is driven out and winds flow in, creating conditions more conducive to fires. Combined with droughts and higher temperatures caused by human-driven climate change, the threat to habitats such as tropical mountain forests has increased.

“This is a huge problem as these habitats are not adapted to fires.”

Unwanted forest fires in Tanzania are often a result of human activities such as farming, honey harvesting, charcoal burning, or efforts to eradicate disease-carrying insects. Other causes include illegal wildlife hunting and arson.

“One major problem was that the monitoring of fire activity in Tanzania was patchy and lacking in detail,” Kabalimu says. “Satellite data can be used to build up a much more comprehensive understanding of fires in the country, and enable authorities to tackle them at the source where necessary.

“Essentially, we want to see less erratic wildfires in the habitats that don’t need them, and more regular, restorative fires in the places that do.”

Just over a decade ago, wildfires in Tanzania were predominantly monitored using networks of lookout towers.

In the dense and mainly inaccessible forests, early fire outbreaks frequently went unnoticed. By the time they were spotted, it was often too late to mount an effective response.

But in July 2011, a satellite receiving station installed in Tanzania’s capital, Dar es Salaam, was opened as part of the European Union’s African Monitoring of Environment for Sustainable Development (AMESD). It was maintained and improved during the EU-funded Monitoring for Environment and Security in Africa (MESA) programme. The initiative was supported by data, infrastructure, technology, products, and services provided by EUMETSAT.

“Information delivered daily by remote sensing technologies can help authorities predict, assess, and respond to the impacts of wildfires,” says Kabalimu.

“Fire lookouts remain an important way of monitoring fires; lookouts know the terrain, and can help direct fire fighting resources.

“However, meteorological satellite data are supporting invaluable additional tools. These include mapping active fires and burnt areas, monitoring changes in vegetation cover, and producing policy planning reports.

“In particular they are proving crucial for community-based fire management approaches. These approaches empower local communities to decide the objectives and practices for preventing, controlling, and using fire.

“In some areas we have seen up to 75% reduction in unwanted fire damage. The impact of these satellite data has been phenomenal.”

Kabalimu says a wide range of heavily forested regions are benefiting from products and services deriving satellite data delivered by EUMETCast. These include the tropical forests of Mount Kilimanjaro, the old-growth forests of Kazimzumbwi, and the forest reserve and plantations of Sao Hill in the country’s south west.

Spanning 135,000 hectares, the Sao Hill forest reserve is a striking patchwork of wide-scale commercial forestry, temperate-tropical forests, and wetlands. Kabalimu says Sao Hill’s state-owned plantation forests are the lifeblood of the local economy, while its habitats help to protect vital water resources used by people across the region.

“The reserve is home to the largest plantation in Tanzania, with a total area of more than 135,000 hectares,” Kabalimu says. “This includes large areas planted with pines, cypress, and eucalypts, but also more than 48,000 hectares of natural forest.

“The presence of this plantation contributes substantially to climate amelioration, water collection, and prevents soil erosion. Sao Hill is home to the source of the Ruaha River that, together with other rivers, is used for power generation. There is also great potential to develop ecotourism in most parts of the forest reserve.”

Kabalimu points out that the region is home to stunning vistas, including Irundi Hill, Kigogo, the Mufindi Escarpment, and the Ihefu Wetlands. But it is the viewpoint of meteorological satellites that are helping to tackle the hundreds of wildfires detected in Sao Hill’s forest plantations throughout the year.

“Since 2011 when forest fire monitoring using satellites was introduced, there have been more than 9,000 fire incidences detected using satellites, mainly resulting from land preparation for tree planting,” Kabalimu says. “Once fire hotspots are identified, a warning message containing their coordinates is sent from Dar es Salaam to responsible local authorities.

“Because we want to get this information out as quickly as possible, this is done using common messaging apps such as Skype and WhatsApp.”

The memos are received by Tanzania’s network of forest managers, including Salum Yakuti who is responsible for managing response teams in Sao Hill.

“There are many ways to carry out early detections, including frequent ground patrols in high-risk areas, a good network of fire lookouts, radio communication systems, and alerts raised by members of the public,” Yakuti says. “And more recently, products and services that derive data from weather satellites have further enhanced our abilities.

“Meteorological satellite data are not only helping teams reach fires more quickly, but also enabling them to plan ahead; the only requirement is a cellular network. This is helping my team to strike a balance between commercial activities and environmental protection.”

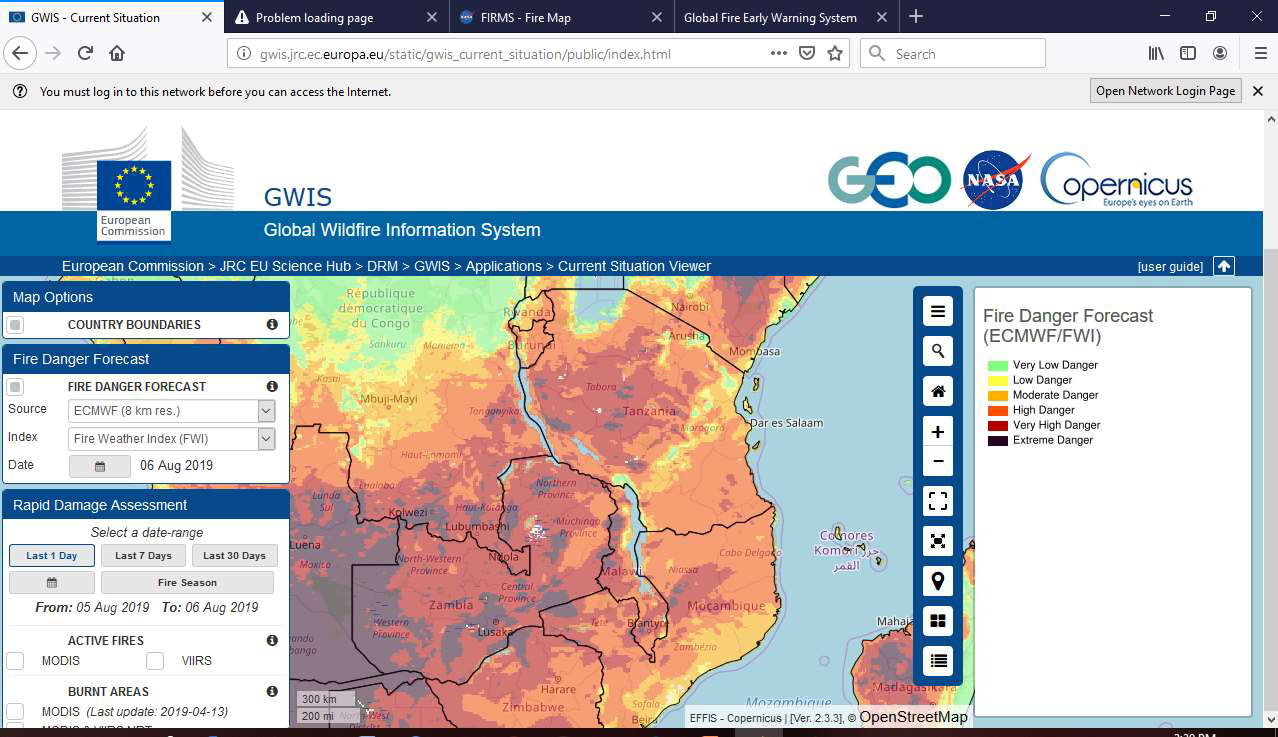

Fire danger indices such as the Global Wildfire Information System combine wildfire-related weather information with satellite-derived data relating to aspects such as vegetation and soil moisture. They give indications of the danger wildfires pose if ignited and feed into products that can warn authorities when fire risks are exceptionally high.

“In Tanzania, forest fires are largely the result of human activity,” Yakuti explains. “Fire danger indices provide opportunities to quantify how favourable conditions are for wildfires to spread or intensify.

“When fire risk is high, we turn to field staff to spread the word, implement and uphold restrictions on fire use where necessary, monitor permits, and ensure regulations are being followed.

“Those who need to use fire are advised and trained to take extra care – for instance, establishing appropriate fire breaks when farming or harvesting honey, or accounting for immediate weather conditions such as high temperatures, humidity, and wind speed.

“Preventing forest fires is in everyone’s interest.”

By combining remote sensing technologies with strategic local approaches, Kabalimu says that fire management will continue to improve.

Her team have delivered training courses to conservation and park managers across the country. The ripple effects are being felt from Zanzibar in the east, to Dodoma in the centre, to Shinyanga in the north.

“So many people are benefiting from these satellite data: from the communities living around protected areas, to farmers preparing crops, to the rangers in our national parks,” Kabalimu says.

“We are able to better manage the restorative effects of fires in some ecosystems and better tackle the devastating effects of unwanted wildfires in others.”

And there is more to come.

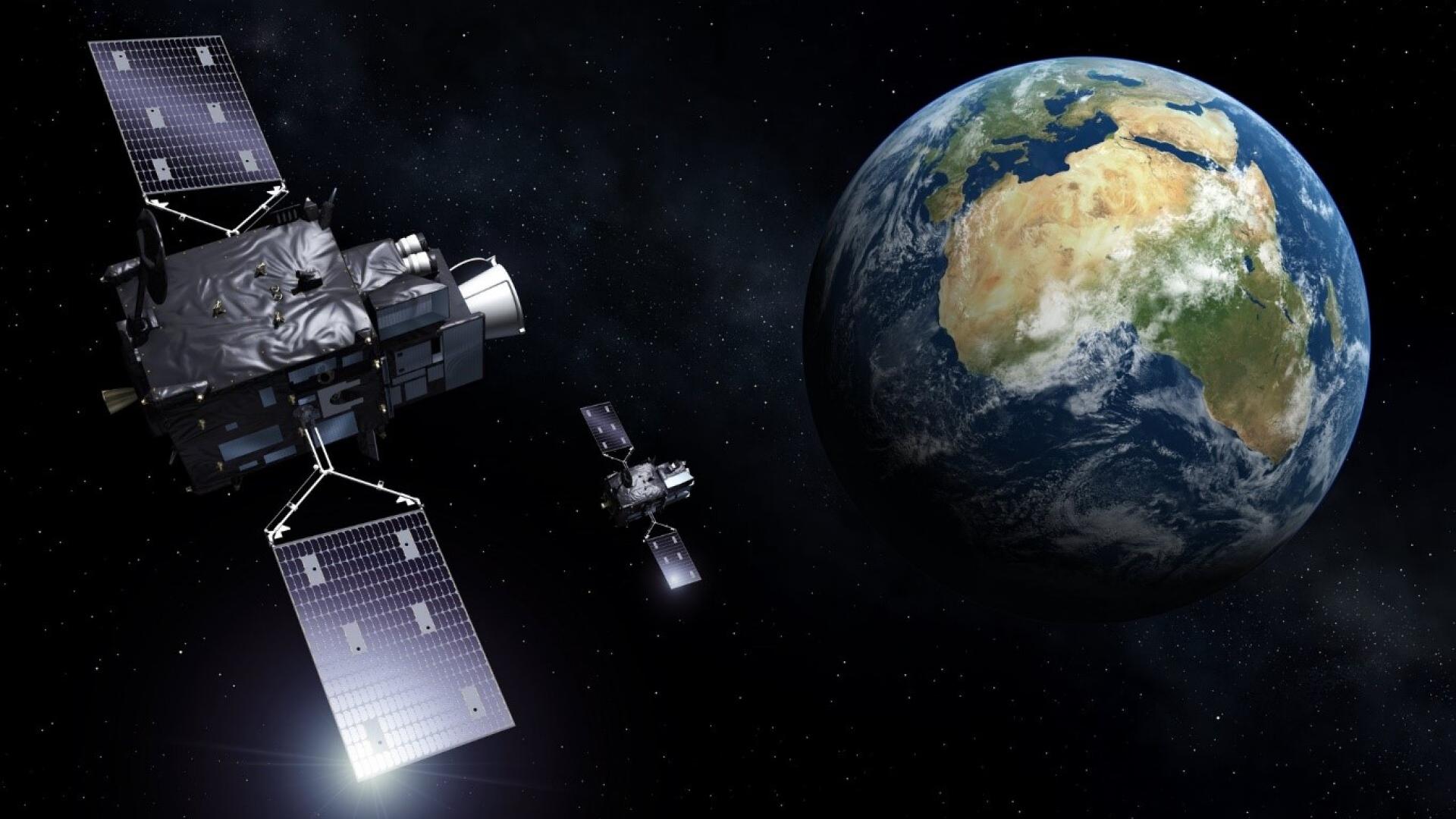

“EUMETSAT’s Meteosat Third Generation geostationary satellites and Metop Second Generation polar-orbiting satellites will provide higher resolution data on wildfire location, intensity, and burnt area,” Kabalimu adds.

“Moreover, a range of important new Copernicus fire products provided by EUMETSAT will further support our work. Collectively these data and tools will boost the way that we manage and tackle fires, assess damage, and ultimately enable us to build a better relationship with fire in Tanzania.”

Adam Gristwood